Inverse Romanticism

In its broader meaning outside the strict terminology of art history, the term romanticism is associated with describing elevated and intense states of imagination, expressed in any medium whatever and with technical or technological supports of any kind. Inverse signifies something subverted or perverted. Here, then, we are confronted with an idea which, right from the start, requires the recipient to have a certain capacity for empathy and imaginative creativity, because imagination-linked (romantic) expressions bring us into a context which “changes the lighting” of the concept and subverts its original meaning (reversal of the code). The term has a dynamic character, because it relates to something and signifies something which is played out in a process and as a process. And where has this term been taken from?

The essential point is that the term inverse romanticism is a product of a curator′s actual practice. It was first used by the curator of this exhibition in 2005 as “romantic inversion”; afterwards in a modified form as “upside-down romanticism”; and finally, in 2008, the exhibition Inverse Romanticism was held in Bastart Contemporary in Bratislava by the artistic grouping of Josef Bolf, Martin Gerboc and Jiří Petrbok (in that same year there was a Prague reprise in Gallery 5). It was only later, after a lapse of time, that the term was comprehended theoretically, with the publication of a book in 2018. That work was produced from a conviction that the given term incorporates an important critical aspect, connected with certain expressions of contemporary visual art which escape the more ordinary critical practice. It was essential to distinguish these from the ‘decadent’ tendencies, whose emergence and widespread media response has supplanted any interest in a deeper theoretical differentiation of the problem in question.

The association of romantic expressions and inverse behaviour can be traced to its basic premises. For the most part, what evokes it is some specifically situated moment, which may have a purely personal, intimate, existential nature, but equally may be socially or historically conditioned. The concept of crisis is often used in this connection, but again this may be bound up with an entire spectrum of causes. The five artists exhibiting here – Ivan Pinkava, Jiří Petrbok, Richard Štipl, Josef Bolf, Martin Gerboc – show aspects of a relationship to some sort of crisis which it is necessary to face. At the same time, this involves “creation”, i.e. activity, which need not be brought to completion and nonetheless comes into being. What it amounts to, then, is an active attitude towards the external or internal stimuli which evoke and sustain this activity, i.e. creation, in a process of continual engagement. The most noticeable aspect, which is common to all five artists, could be described as a crisis of the representative capacity, i.e. representation which would have support in the responses of the majority society. On the contrary, the position is that the majority society normally tends rather to reject the works of these artists; has no thought of finding common ground with them; considers them shocking, destructive and (quite unjustly) “decadent”. The problem of misunderstanding (or lack of appreciation) is then transferred to other, social levels. There it is generalised and designated as a problem associated, firstly, with a revaluation of the role of art and the artist in human society, i.e. with their social identity, and secondly, with a transformation of the expressive means which are the bearers of this problematic representation. Hence if representation is to be possible using those means of expression, that depends on the measure of communicative openness that is cast abroad into a world of differently perceiving beings, and equally into the inhospitable media space, which reproduces, caricatures and reduces whatever it takes in as raw material to broadcast and distribute (to and from the majority society). The media space itself is filled with a rationally directed process which in its own manner systematises whatever it disseminates.

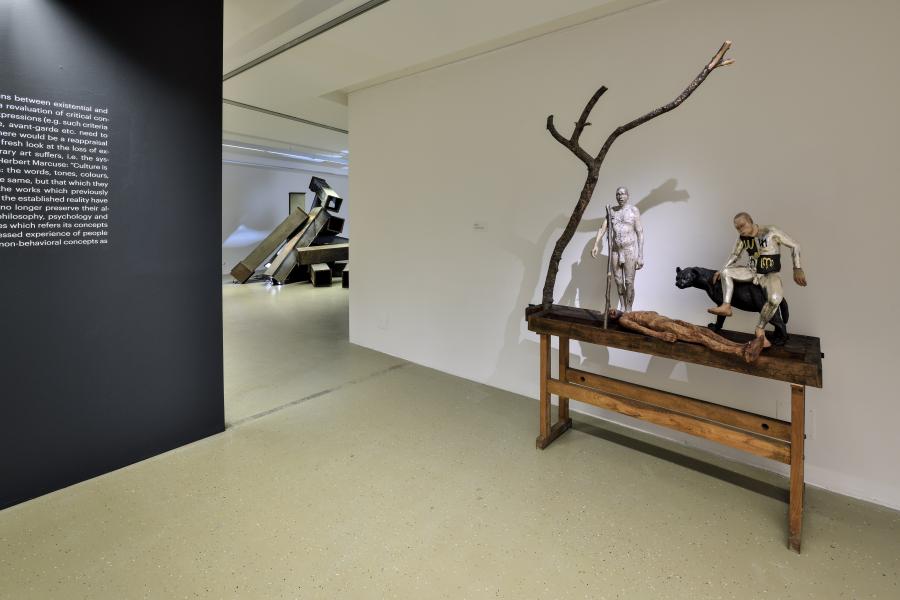

In this connection one can name a further aspect of crisis: problematised non-verbal, purely visual communication which cannot be purely passively consumed by the viewer. In the work of all five artists it acquire a specific form, on the level of a critical expression which is ceaselessly assembling and collapsing. There is a marked inclination towards morphological hybridisation; a refined or violent fusion of heterogeneous expressive means (deformation, exalted colourfulness and expressiveness, vanishing, superimposition, construction of acknowledged models); inflamed imagination, irritation, creating phantoms and monsters that might be caricatured representative figures (including their own face-studies and self-portraits); dramatisation of pictorially reduced situations, theatricality, artificial arrangements, and also evocations of awkwardness, irony, powerlessness and perversity, which in varying degrees contaminates the process of creation.

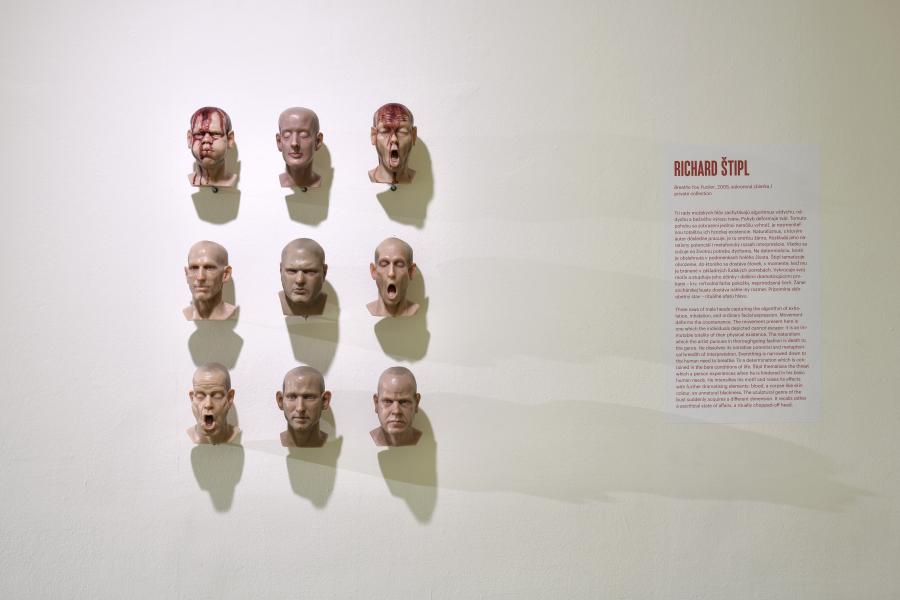

On the other hand, there is an evident tendency to balance the unleashed pathos with polarising elements. The latter to a certain extent check, subdue or neutralise the exalted expression, and thus communication is confined to the form of a functioning dialectical framework, to a formally unified contradictoriness (or allegory) which may be communicated as existential experience (e.g. Martin Gerboc’s cabaret form, Richard Štipl and Jiří Petrbok’s altar forms, the archaic and theatrical residues in Ivan Pinkava, and Josef Bolf’s hybrid stylisations).

The borderline which is tracked here runs between existential and false narration, and it ought to lead to a revaluation of critical concepts in the reception of these artistic expressions (e.g. such criteria as conservative, progressive, regressive, avant garde etc. need to be rethought). Corresponding to this, there would be a reappraisal of the artistic legacy of the past, and a fresh look at the loss of expressive validity from which contemporary art suffers, i.e. the systemic instrumentalisation described by Herbert Marcuse: “Culture is redefined by the existing state of affairs: the words, tones, colours, shapes of the perennial works remain the same, but that which they express is losing its truth, its validity; the works which previously stood shockingly apart from and against the established reality have been neutralised as classics; thus they no longer preserve their alienation from the alienated society. In philosophy, psychology and sociology a pseudoempiricism dominates which refers its concepts and methods to the restricted and repressed experience of people in the administered world and devalues non-behavioral concepts as metaphysical confusion.”

But what unceasingly returns, and is renewed with each generation, is the “instinct of curiosity”. Necessarily it is attended with phenomena that are constantly repeated. And it is precisely these (they are observable, for example, in contemporary painting, photography, sculpture), surfacing as they do from what is at first the unclear entirety of an apparently banal series of indications, which are determinant for the orientation of contemporary art. Repetition has a dual nature, going in contrary directions. One kind of repetition founds the standardisation of art, its social establishment, its unification and conformity by means of artistic traffic and the institutional background. The second, however, creates a countermovement based on negation. This is not necessarily a direct negation of the established order, it need not be deliberately aimed at the operative system: it is simply what has developed in its own specific artistic manner and integrates other experience which leads to taking a different course: outside the system (alternative) or also against it (pure negation). As compared with the well-defined subcultural artistic activities, such countermovements can be entirely unconscious, subliminal artistic expressions (poetic imagination), constantly, even obsessively returning to a circle of what are always the same themes and motifs. These are elaborated and deepened by creative work, and this occurs without any outside pressures or recommendations, outside the educational institutions and with a risk of social sanctions. Their task is (whether consciously or unconsciously) to contain and preserve elements of the Marcusean non-operational dimension of culture, namely, what there is in culture that society cannot convert to a unifying and universally applicable equivalent of instruction, upbringing, work, comfort and self-representation, and which thus for many reasons finds itself beyond the reach of social control.

In the work of all five artists exhibiting here one may find traces of inversion, which as negation dissolves, and which composes what it negates so that a space may be opened for the critical movement of creative work and thinking. Here, then, is where we may find inverse romanticism, the concept we have been following, in situated form. Romanticism in the work of these artists is a risky movement on the frontier of so-called “perverse infinity”, which like a black hole threatens to pull the artist beyond the world of soluble problems.

Inverse procedures in contemporary visual culture, despite their unclear definition and diverse character, have the capacity to demarcate their workings and defend a distinctive artistic space for free creation, even in an inhospitable milieu which seems hostile to any such efforts. And ultimately these procedures have an opportunity in their own way to exert influence on this milieu, or (a better way of putting it) to seek prototypes of a reform, which may be shown or depicted in positive and negative outlines.

Petr Vaňous

Exhibition curator and also author of the book project

– – – – –

Facebook event

– – – – –

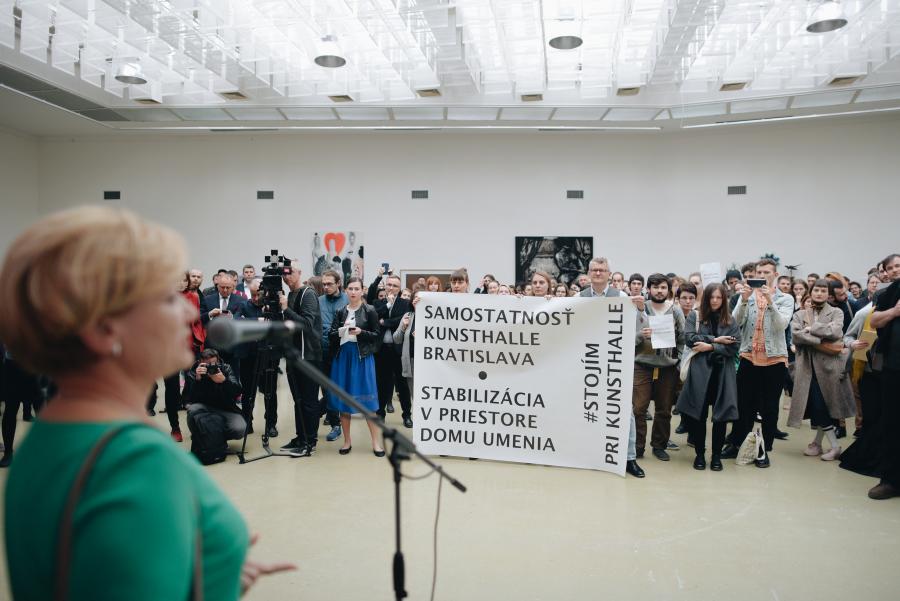

The exhibition Inverse Romanticism follows on from the identically-named book project and is its repeated translation to the exhibition medium.

The exhibition is suitable for visitors older than 18 years old.

– – – – –

Exhibiting artists:

JOSEF BOLF (*1971, Prague, Czech Republic) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (1990 – 1998); the studios of the Professors Jiří Načeradský, Vladimír Kokolia and Vladimír Skrepel. In 2005 he became a finalist for the Jindřich Chalupecký Prize, and in 2010 he won the Person of the Year Prize. He was a member of the Headless Horseman group (active from 1998 to 2002). Since 1998 he has exhibited regularly. Josef Bolf’s painting is a large and thoroughgoing work of introspection. Its distinctiveness is founded on expressive techniques of drawing and painting which have have a strongly personal artistic quality. Introspection, combined with the expressive means, creates an entire unique, intricate and complex personal mythology.

MARTIN GERBOC (*1971, Bratislava, Slovak Republic) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava (1990 – 1996), where he completed a programme of doctoral study (2001 – 2004). Alongside his activities in the field of visual art, he is the author of several books. He is active as a curator, publicist, and author of song lyrics, video clips, film projects, etc. Since 1991 he has been exhibiting regularly. Martin Gerboc uses the painting as a raw resource and a structural material given shape by violence, where he allows himself also to appear and disappear as in a labyrinth (presenting frequent self-portraits in various situations). This artist affirms the power of visuality as such; painting for him is ultimately more a directing platform for a quest for new modes of emphatic narration, rather than an aesthetic ambition.

JIŘÍ PETRBOK (*1962, Kladno, Czech Republic) was employed in n. p. Buzuluk Komárov as a locksmith, later as a draughtsman (1979 – 1983). He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (1984 – 1991); the studios of the Professors Radovan Kolář and Jiří Sopko. In 1997 he became a departmental assistant in the Studio of Drawing at AVU, and since 2011 he has been head of this studio. He has been exhibiting regularly since 1991. “Beauty” is something which Petrbok discovers in difference, including extreme forms. Knowledge loses its ideal framework and becomes a permanent metamorphosis; characteristic of this is a different type of speed (speed too has a libidinous character and may be a pleasure) and dynamics, different from the limpid movement of the Renaissance and all that is mechanical and regular, all that uses calculating reason to classify and articulate space and time in acceptable and clear sections, ratios and relationships.

IVAN PINKAVA (*1961, Náchod, Czech Republic) studied in the Department of Art Photography at the Film and Television Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (1982 – 1986); afterwards he worked as a freelance photographer, with the exception of the years 2005 – 2007, when he was head of the Studio of Photography at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. He has exhibited regularly since 1988. An internationally respected photographer, Ivan Pinkava has had a long-term focus on a certain circle of questions, which he projects into chosen themes. Taking an overall view of his photographic work, it is evident that one of the most essential components in the artist’s work is reduction to a purely static image. There is a need to choose only what is most fundamental, whatever in the photograph would be capable of sustaining comprehensible content and at the same time would veil it in allegory, ambiguity, and irritating mystery.

RICHARD ŠTIPL (*1968, Šternberk, Czech Republic) graduated from the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, where he received an honours diploma in 1992. In the early years of the new millennium he frequently presented his works in New York and Toronto. He has been exhibiting regularly since 2002. As a sculptor, Richard Štipl works with an inversion of self-resemblance and sameness. The human figure is a fundamental symbol for knowledge, based on the principle of self-admiration: knowledge through the self (one’s own and alien corporality, which is identical). Stipl’s work is developed in traditional materials (wood, metal) and in the disciplines of figure and relief. The way they are handled, however, is not so traditional. Rather, it is inverted. Powerful sources of inspiration are evident in late Gothic wood-carving (especially in relief formats) and in the expressively tuned registers of baroque naturalism (e.g. Franz Xaver Messerschmidt).

Curator:

PETR VAŇOUS (*1975, Kuntá Hora, Czech Republic) is a historian of art, curator, theoretician, and critic of visual art. He attended the Václav Hollar School of Fine Arts in Prague (1993), continued his studies at the Department of Theory and History of the Visual Arts at the Philosophical Faculty of Palacký University in Olomouc (1993 – 1999), and subsequently completed a doctoral study in the Department of Critic and Theorist of Design and Intermedia at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (2010 – 2015). Since 1999 he has worked as an independent curator. He studies the relationship of traditional visual arts media (especially painting and drawing) and the new visual trends, focusing on the changes in painting and drawing under the conditions of the information society and universally diffused media (the so-called ‘post-media situation’). He is the author of numerous exhibitions and exhibition projects.

– – – – –

Inverse procedures in contemporary visual culture (web news)

Inverse romance (artfacts)

Romance as you don’t imagine it. Kunsthalle Bratislava has a new exhibition (We are)

Martin Gerboc: It is unbearable for a viewer to be helpless at once (SME)

Only over 18 years of age: The exhibition Inverse Romance was opened in Bratislava